McDonough County’s business history is so extensive that it could take a lengthy book to discuss the subject. This brief overview will just emphasize various kinds of business enterprises that had an impact in the nineteenth century.

Of course, our villages were initially characterized by locally created stores, restaurants, and hotels— in an era before national chains were developed. For example, an 1872 Macomb photograph here shows East Jackson Street, entering the square—when the unpaved roads were all muddy due to a recent rain. On the left is George W. Bailey’s dry goods store, which had been built in roughly 1840, when small frame structures were replacing log ones. And across the street is Joe Adcock’s grocery store, which opened in mid-century. As I mention in Macomb: A Pictorial History (1990), “In 1852, there were, in fact, nine dry goods stores, two other clothing stores, two shoe shops, two drug stores, eight blacksmith shops, and various grocery stores, offices, and manufacturing places.”

Indeed, plows and wagons were made on or near the square, due to increasing demand as the number of farms rose continually. And those were common products available at most Illinois county seats.

Macomb also had a couple very early hotels (which were at first called “taverns”), and they helped to popularize the community. Pioneer James Clarke opened the initial one, on the square, in about 1830. It was a sizable log building, and as its owners changed, it was remodeled to become George Head’s Tavern and then a hotel called The McDonough House. It had 26 rooms, and the early stagecoach lines regularly stopped there. By the mid-1850s it was a substantially brick building known as The Empire House, and many local residents knew it well because annual balls that drew community-wide participation were also held there. The other very early hotel was a frame building called The Green Tree (1835), which was later known (in the 1840s) as The Macomb House and then (by the mid-1850s) as The American House.

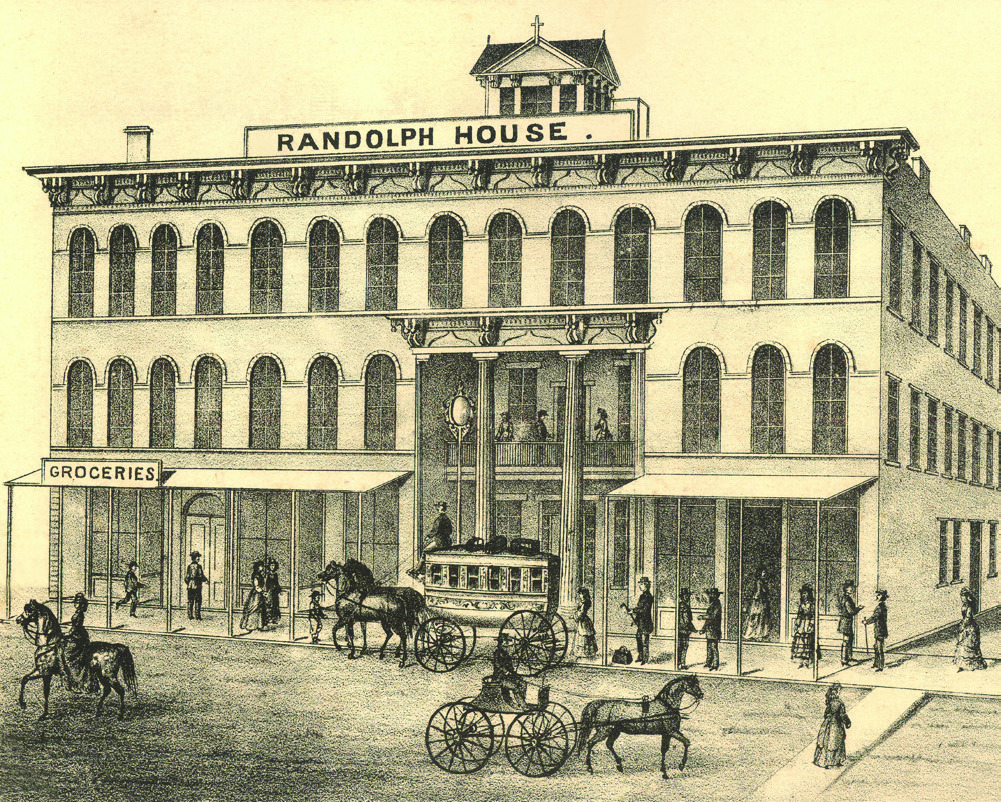

As most residents today know, the most famous nineteenth-century hotel was The Randolph House, an elegant, three-story brick building constructed by a former sheriff, circuit clerk, and state representative, William H. Randolph.

It opened in 1857, at the southeast corner of the square. As I point out in my Macomb history, “it had a level of elegance almost unheard of in western Illinois.” Since the railroad had recently come through, the hotel even had an omnibus, pulled by two black horses, which took guests to and from the depot, located west of the downtown. Lincoln stayed there twice in 1858, so the old hotel building has historical significance. Even though part of the building was torn down generations ago, his room remains.

At that time, Macomb’s most prominent early downtown businessman was N. P. Tinsley. In 1836 he had come to Macomb, where he initially operated a log cabin general store. A year later, he constructed a frame building on the north side of the square.

According to an 1851 ad, his general store sold clothing, blankets, shoes, hardware, and groceries—“all of which will be sold cheap for cash . . . and for most kinds of produce, such as Pork, Lard, Bacon, Wheat, Corn, Oats, Butter, Flaxseed, Hides . . . etc.” So, folks often traded their home products for store goods.

Tinsley also constructed the first steam-powered mill in the county, on South Randolph Street, where area residents could get their corn and wheat ground. In 1857, as his business boomed, he replaced that mill with a larger one. And he was later a wealthy co-founder of the Union National Bank—and was well-known for his public interest and helpfulness to others.

Tinsley was also a pork packer—as were members of the Bailey, Lawson, and Wells families. In that early era the area farmers butchered their own hogs, and then hauled them to Macomb by wagon, where the packers cut up the carcasses, put that meat into barrels, and took it to the village of Frederick, on the Illinois River, where it was shipped to St. Louis. The area later known as Chandler Park was central to that local effort—and was noted for its stinky smell.

Also related to agriculture was the business of two noted local pioneers in farm machinery, John Wiley and Charles Dallam, who came from Martin’s Ferry, Ohio, in the early 1840s.

They manufactured the first threshing machines made in McDonough County. Wiley also bought 320 acres of raw, unbroken prairie land, four miles east of town, and turned it into one of the largest farms in the early county. Dallam also went into partnership with N. P.

Tinsley to establish a steam mill north of Macomb, and he managed that operation for many years.

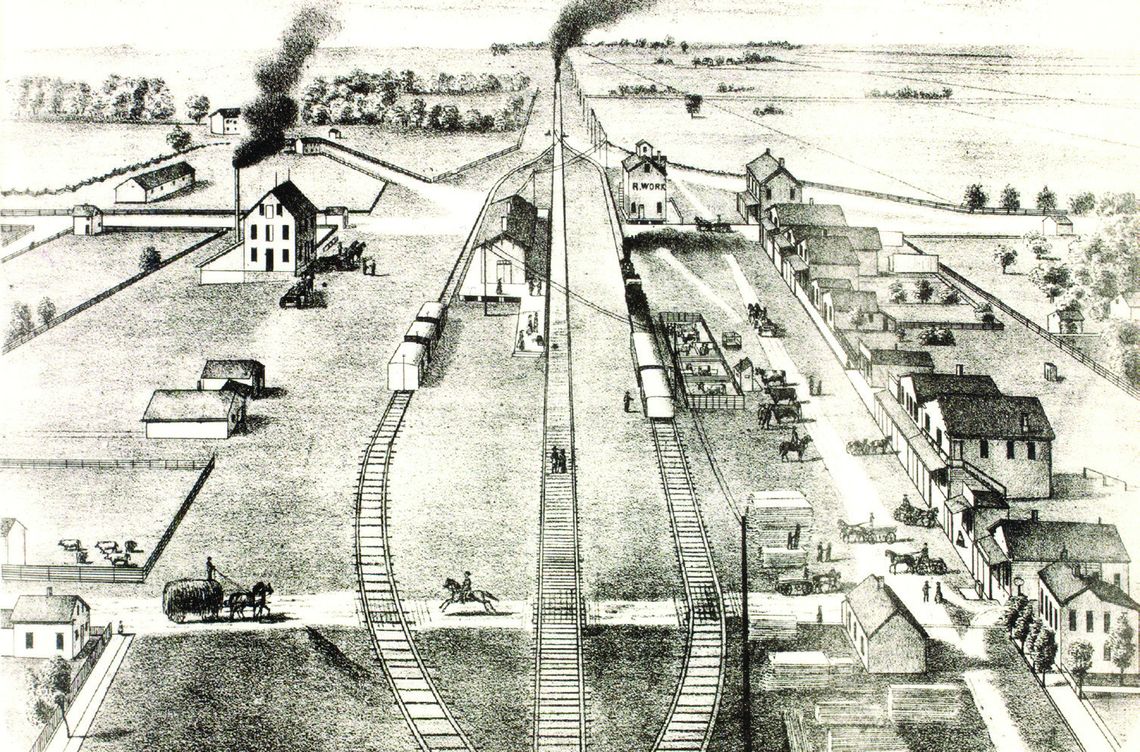

Of course, the coming of the CB & Q (Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy) Railroad, in the later 1850s, had an impact on the shipping of both livestock and other products—from Macomb and smaller towns. In Bushnell, for example, access to cities by railroad shipping prompted a successful early business, the Ayres and Decker Company, which made barbed wire fences.

McDonough County also had some very successful horse breeders, including such figures as Jonas Lindsey, who bought horses imported from England, and J. N. Rexroat, who bought horses imported from France. In 1882 the Macomb Journal declared that Macomb “contains a larger number of importers and breeders of European draft horses than any other place of its population [i.e., any small town] in America.”

That reputation surely prompted another, more noted breeder, to operate in Bushell: Jonathan Hall Truman (who had been raised in Cambridgeshire, England). In 1883 he established the Truman Pioneer Stud Farm—which imported notable breeds of draft horses from England and also sold American horses in many locales. He had five sons who were eventually leaders in that company, too. As the 2004 history of Bushnell by Rollene Storms (edited by Peggy Hood) indicates, “By the early 1900s, the farm had nationwide acclaim, and the Trumans were known as ‘America’s Largest Horse Importers,’” so Bushnell was often labelled as ‘The Horse Capital of the U.S.A.’” Indeed, as she also reports, at the 1904 World’s Fair, in St. Louis, the Truman company entered 25 horses and “won six gold medals, plus eight other awards.”

No wonder that by 1908 there was a very popular annual Bushnell Horse Show in that small town, held during October. It featured a big parade, led by the Bushnell Band, and horses from various places were displayed and judged, for the distribution of several thousand dollars in awards.

Some fifteen thousand people often attended, and local schools were also shut down. The Truman Stud Farm, and the company’s horse show, made Bushnell one of the best-known small towns in Illinois. Of course, the coming of cars, trucks, and tractors later unfortunately diminished the need for work horses.

Other noted businesses in that community were Vaughan and Bushnell (which produced tools), Ball Brothers (which produced a variety of wagons and carriages), and The Bushnell Pump Company (which not only produced wooden and iron pumps but tanks and windmills).

Another town that was deeply influenced by the coming of the railroad was Colchester. Some coal mines had opened there in 1854, so the town was platted in the following year. A few years later, the first shaft mines were sunk, and large-scale coal mining developed. Participation in that enterprise helped to foster a sense of community for many Colchester residents. As I mention in The Bootlegger (1998), by the 1870s there were also occasional deaths from coal mining accidents. But by the 1880s there were many other businesses in that coal mining village—and “It seemed to be a place of real promise.” Business leaders also produced and shipped out livestock, flour, and bricks, as well as coal.

Yet another village with well-known businesses was Bardolph. In the late nineteenth century it had a variety of dry goods stores, hardware stores, drug stores, and restaurants. But its most noted businesses were devoted to manufacturing pottery ware and tile products. Indeed, that town had one of the largest tile plants in Illinois: the Bardolph Fire Clay Works.

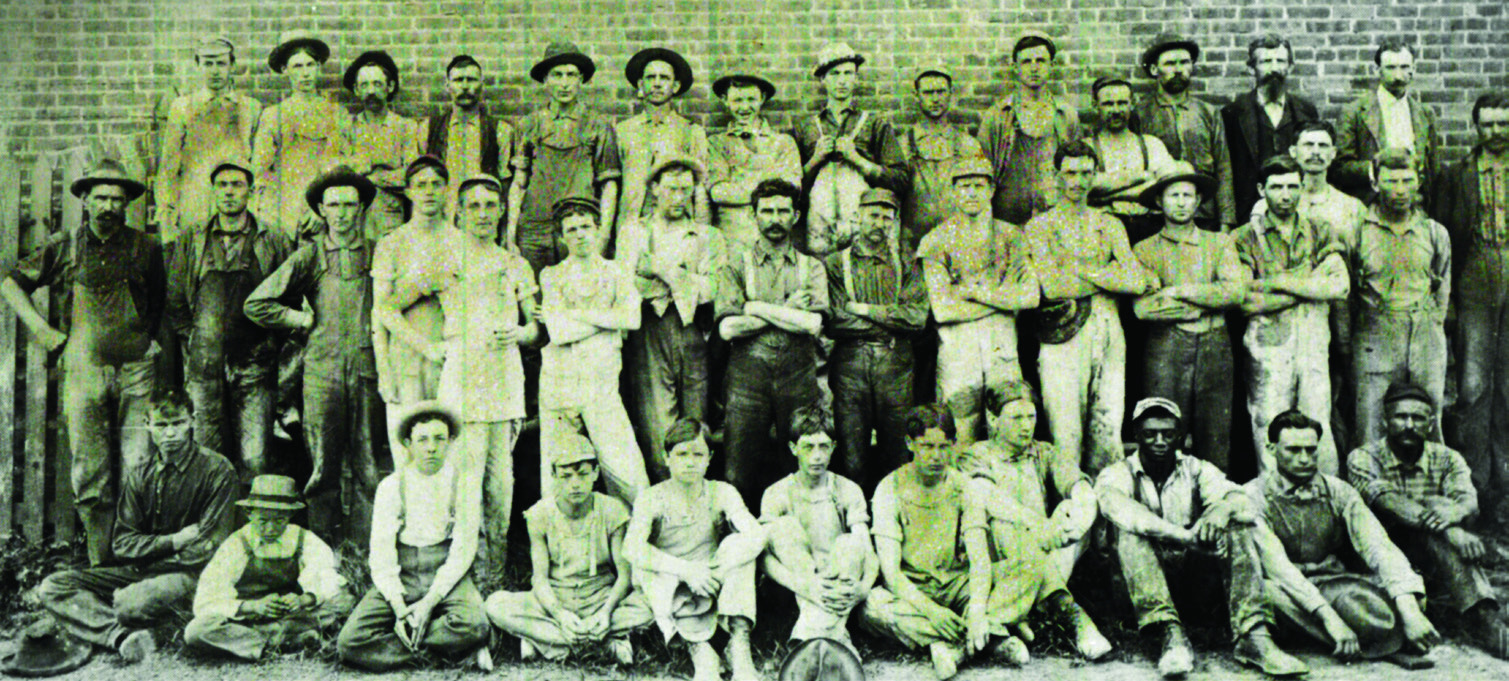

Of course, the most prominent manufacturers in late nineteenth-century Macomb were also pottery factories. The first one, created in 1873, produced a variety of pottery, from clay mines developed northeast of Macomb, but it lasted for less than ten years. A second one, soon named Eagle Pottery (in 1876), manufactured jugs, jars, crocks, vases, flower pots, and other ware, which were all shipped out by rail. That led to a new, bigger plant, supposedly “the largest stoneware plant west of Ohio”—as I mentioned in my history of Macomb. It soon became known as The Macomb Pottery. In the early 1890s The Buckeye Pottery was also established. And in 1890 The Macomb Stoneware Company began as well. Located between North Campbell and North Dudley streets, it soon became Macomb’s largest pottery manufacturer. An 1898 photograph of the workers for that company is also included here.

The 1890s also brought two sewer pipe plants to Macomb, which were huge, So, by the close of the century, Macomb produced more clay products than any other community in America, except Akron, Ohio.

All of this reveals that McDonough County was very well-known for manufacturing before the twentieth century, so the later development of notable Macomb factories, such as Hemp Company (which made kitchen chairs, stools, ovens, and thermos jugs), Illinois Electric Porcelain (which made insulators for electrical and telephone companies), and Haeger Pottery (the world’s largest maker of art pottery), were part of a long local-manufacturing tradition. And the town’s biggest modern factories, the NTN Bower Corporation (known for its roller bearings) and the Pella Corporation (which makes windows and doors), are part of that tradition, too.

As this overview indicates, McDonough County generations ago was not just devoted to agricultural production, and even in the nineteenth century this corner of America was well-known for coal mining, horse breeding, pottery making, and various manufacturing enterprises.