The idea came to Western Illinois University History Professor Peter Cole during a trip to Berlin in 2017. The public art projects dedicated to the Holocaust in the German capitol brought Cole’s attention back to his home country and the lack of recognition of “historical atrocities” that occurred on American soil.

“One such example in Berlin is called Stolpersteine or stumbling stones. German artist Gunter Demnig started installing small brass plaques outside of the last known home of Holocaust victims, and there are now more than 100,000 Stolpersteine across Europe in places where the Holocaust happened,” Cole explained. “I was deeply impressed by Demnig’s public art project, as are many. I also couldn’t help but note that the U.S. does a horrible job at remembering the history of our country’s atrocities, such as the genocide of indigenous peoples and enslavement of millions of Africans. Having taught at WIU since 2000, I knew my students had zero knowledge of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919, despite it being the worst episode of racial violence in that city’s history; it’s not their fault, they weren’t taught it. Historians know this history but few other people do. I figured we could install 38 markers in Chicago sidewalks–where each person was killed–to uplift this history that has been hidden, essentially, in plain sight.”

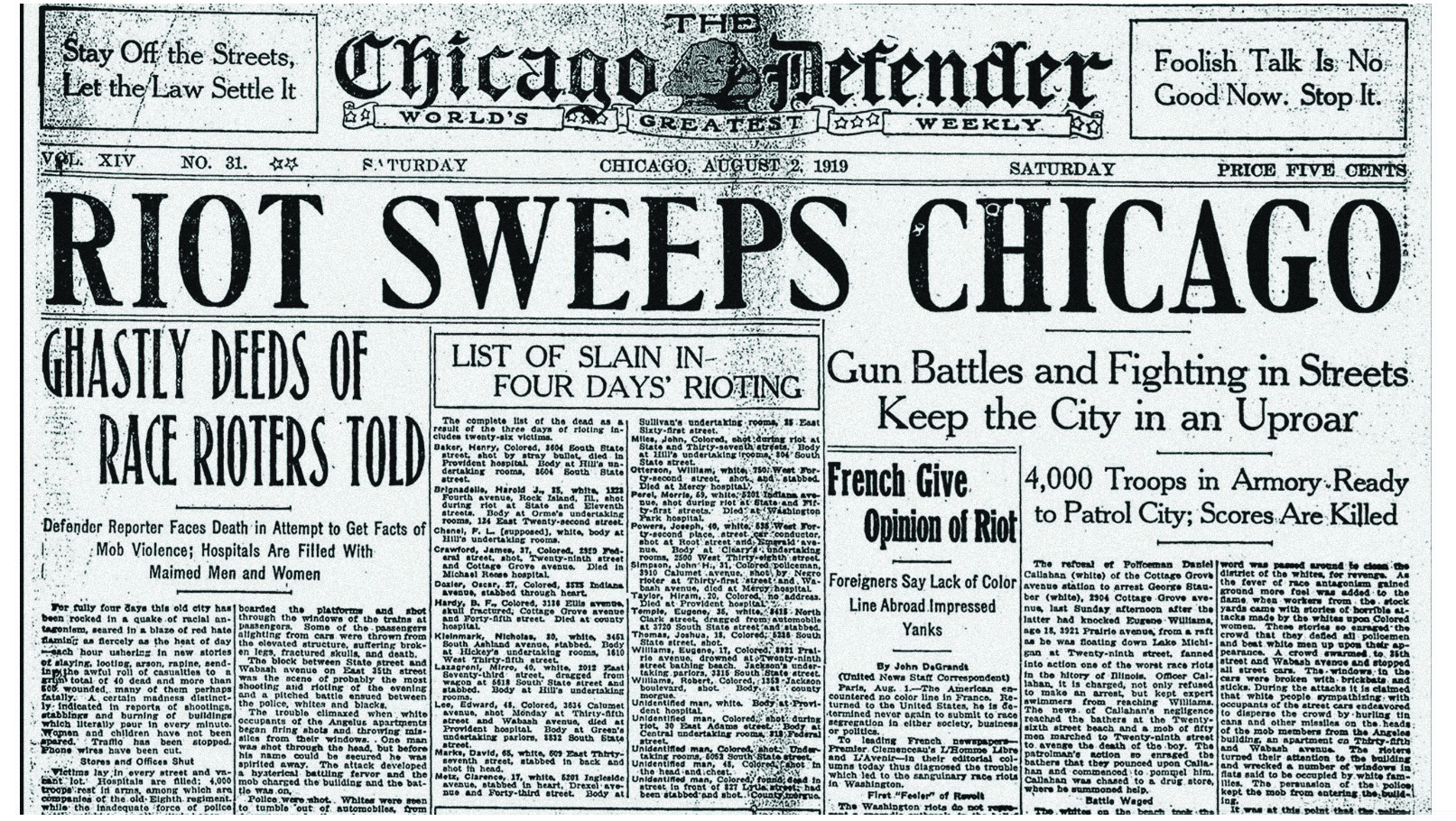

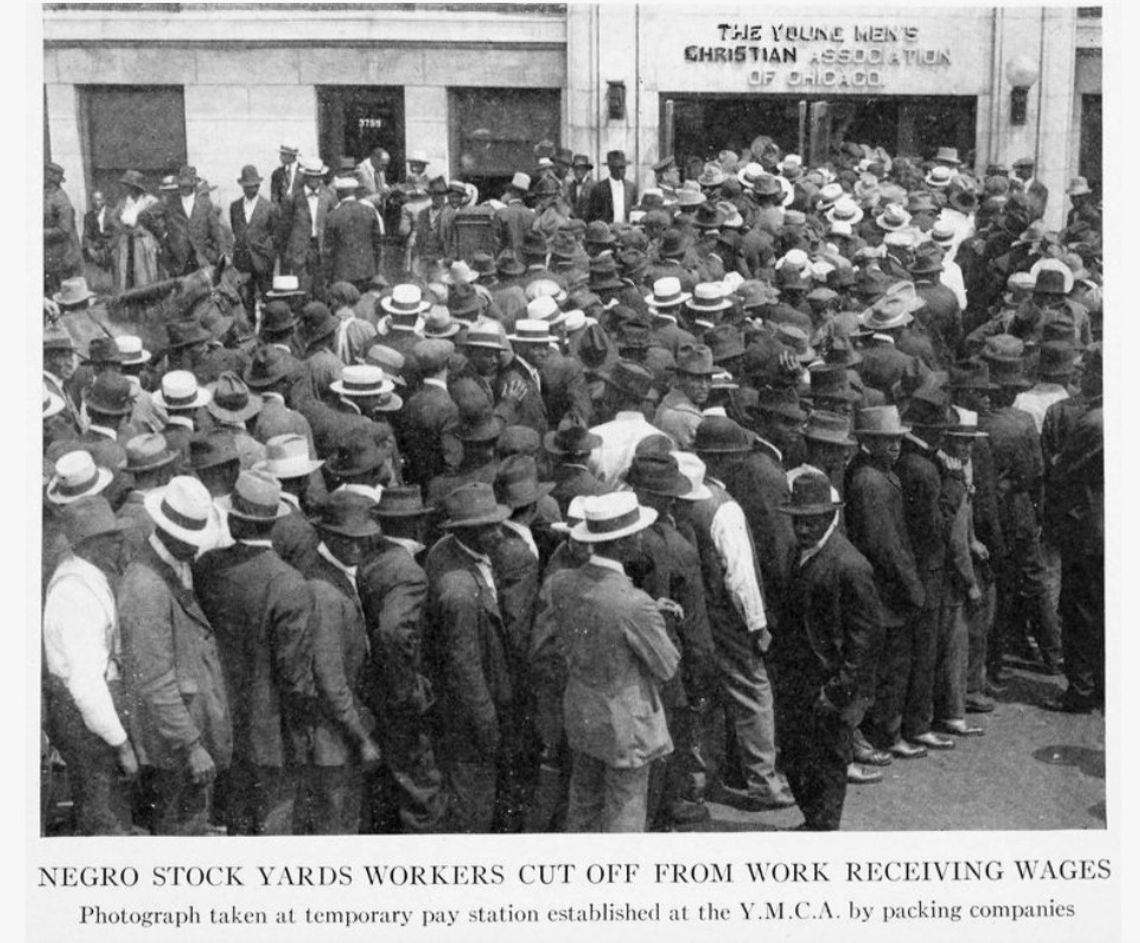

Cole founded the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project (CRR19) in 2019, 100 years after what is known as the “Red Summer of 1919,” one of the bloodiest periods of racial violence in 20th century America. During the Chicago Race Riot, 38 people were killed and 537 people were injured as mobs rampaged through much of the city for an entire week. Last month, Cole hosted a panel discussion and walking tour to commemorate the event in U.S. history. To date, 19 of the 38 markers have been installed to recognize those killed in the riot. The project is a collaboration between CRR19, Organic Oneness and Firebird Community Arts. Marker installation is led by Engage Civil and Trice Construction.

“We were thrilled to organize this historical walking tour and panel discussion with some of the artists who designed our markers. We also created this event in order to feature three of our most recently installed markers, which are in Chicago’s famous downtown, the Loop,” he shared. “Since the Loop draws so many thousands of people each and every day, these markers likely will receive greater attention than the rest which are scattered across various south and west side neighborhoods.”

The recent tour began at the Harold Washington Library, the main branch of the Chicago Public Library, as it is located where one person was killed, followed by a walk to two other markers. Aldermen Lamont Robinson and Bill Conway (whose wards are part of the tour), as well as Deputy Mayor of Community Safety Garien Gatewood, joined Cole. The tour also stopped along the way to feature other public art, specifically several new murals that celebrate the women who fought and won the right to vote in 1920 including Chicago’s Ida B. Wells-Barnett, who fought for racial and women’s equality, and was the leading investigative journalist investigating the “red horror” lynchings.

To date, $400,000 has been raised to install the first 19 markers. Funding comes from individual donors, grants from such organizations as Illinois Humanities and the City of Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) via the Chicago Monuments Project. The Chicago Monuments Project received a major donation from the Mellon Foundation, Cole noted.

From a researcher’s standpoint, Cole said the Nov. 8 walking tour was impactful because of its location in Chicago’s Loop. The 16 other markers have been in place for some time, but have received far less attention, he noted.

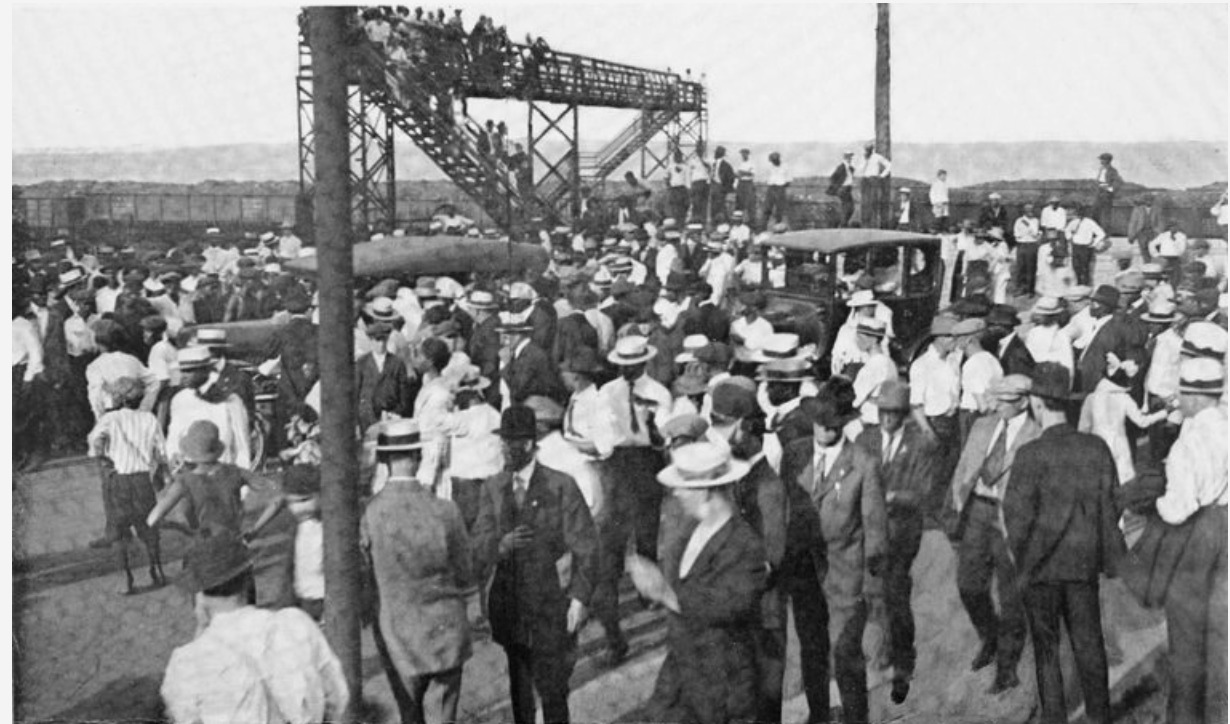

“This most recent event was significant because half a dozen of the artists, who are part of Project FIRE at Firebird Community Arts, participated. Our artists are young Chicagoans, men and women, who have survived traumatic incidents of violence,” Cole pointed out. “The first person killed in 1919 was Eugene Williams, a 17-year-old Black boy. He was swimming with friends in Lake Michigan on a hot summer day when they drifted across an invisible line in the water and a white man started throwing rocks at these children for breaking the customary rule that racially segregated Lake Michigan. No laws discriminated based upon race in Chicago or Illinois, but unofficially racial segregation was the norm, which is called de facto segregation. Eugene Williams was murdered simply for being in the so-called ‘wrong’ part of the lake.”

When a white police officer refused to arrest the killer who had been identified by Williams’s friends, and also refused to let a Black police officer arrest the killer, violence escalated, rumors spread and white ethnic gangs started attacking more Black people that same night.

Each year since launching the project six years ago, Cole, CRR19 Co-Director Franklin Cosey-Gay and their partners have hosted a bike tour near the anniversary of Williams’s murder; they also offer historic tours by bus and foot. Avid cyclists, Cole’s and Cosey-Gay’s favorite way to share the route is by bicycle as it is easy to cover a few miles, while stopping to see the markers and learn more. These tours explore the history of 1919, its legacy – which was a widening and deepening of residential segregation – and the beauty and resilience of Chicago’s Black community.

“We mostly offer tours in the Bronzeville and Bridgeport neighborhoods, which are side-by-side, are where most of the violence occurred in 1919 and have a long history of deep residential segregation ever since,” Cole added. While Cole and Cosey-Gay, who serves as the executive director of Community and External Affairs at the University of Chicago Medicine’s Urban Health Initiative and is the former director of the University of Chicago Medical Center Violence Recovery Program, are dedicated to ensuring the history of Chicago 1919 lives on in history, Cole also wants people to be more aware that horrific race riots – often more recently referred to as race massacres, he noted – occurred in East St. Louis and nearby Springfield. Last year, the CRR19 team partnered with scholars at University of Illinois-Springfield and Southern Illinois University- Edwardsville to secure a major grant from the Illinois Innovation Network (IIN) that was used to fund the travel of 40 individuals from Chicago, East. St. Louis and Springfield to Montgomery, AL, the home to the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial to Peace and Justice, nicknamed the National Lynching Memorial.

The work, led by Cole, University of Illinois Springfield (UIS) Associate Professors Devin Hunter and Lesa Johnson and Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Assistant Professor Tandra Taylor, “Journeys to Justice: Commemorating and Memorializing the History and Legacy of Anti-Black Terror in Illinois,” launched a statewide initiative to promote and support the research and remembrance of anti-Black riots, massacres and lynchings in Illinois.

“Offering this free experience to Illinoisans was an incredible way to show people in the Land of Lincoln another example, perhaps the best in the nation, of how a community can remember something horrible. Once we acknowledge such histories and learn from them, we can finally move towards healing which has been delayed for far too long,” Cole said. “Of course, if our country had no racial problems, perhaps we wouldn’t need these history lessons. However, if the massive, largely peaceful protests that happened in 2020, after George Floyd was murdered by police, taught us anything, it’s that our country still has a long way to go until we’re all free. So, too, the 2024 murder of Sonya Massey, a Black woman, by a white Sangamon County deputy sheriff.

“Public art is such a wonderful way to uplift history because public art is free and accessible, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year,” he concluded. “Before a community can be truly just, we must heal from historic atrocities that have divided us.”

To learn more about CRR19 or make a donation, visit chicagoraceriot.org.