Macomb-born Albert Omega Sears was a saxophonist during the height of the country’s jazz era, and he helped usher in the new style of music called rock and roll. A man with perfect pitch and a master of rhythm, he was a leader in music performance and business.

Sears began making history when he was delivered by Macomb’s first female physician, Dr. Elizabeth Miner. On Feb. 21, 1910, he became the eighth child born to Martha (Miller) and John Sears. The family lived in a home that no longer stands at 712 E. Adams St., in a neighborhood on the east side of Macomb that was historically home to the city’s Black community. Later, future civil rights leader C.T.

Vivian lived on the same block.

A minister, John Sears moved his family in 1918 to Zanesville, Ohio, where he became superintendent of a mission.

1920s

Also a musician, Sear’s older brother Marion encouraged Sears to pursue music.

While in his mid-teens Sears had a brief gig playing saxophone with Fats Waller in Harlem. At 18, he replaced Johhny Hodges in Chick Webb’s band and played in the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem.

This led to Sears joining the traveling Black Broadway musical “Keep Shufflin’.”

The show was financed by Arnold Rothstein, a gangster who was reputed to have fixed the 1919 World Series.

Funding ran out while the show was in Chicago, but Sears soon found a job in 1929 with Zack Whyte’s Jazz Orchestra in Cincinnati.

1930s

Sears played with multiple bands in Cincinnati, Buffalo and New York City.

His work was noticed by John Hammond, a wellknown jazz promoter who is credited with discovering Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, County Basie, Aretha Franklin and others.

By 1937, Hammond was acting as Sears’ manager and had obtained dates for him to play with Harry James, whose band recorded with Frank Sinatra.

A job with Vernon Andrade’s dance band gave Sears steady employment in New York City, where he played regularly during the late 1930s at Harlem’s Renaissance Ballroom. He usually played alto saxophone in the band until midnight and then jammed on tenor sax for hours at a jazz club.

1940s

During World War II, Hammond helped arrange for Sears to lead a band on a USO tour of military bases and camps. The favorable publicity from that tour led Sears to get subsequent gigs, first with Lionel Hampson’s band and then with Duke Ellington’s orchestra.

He replaced Ben Webster, Ellington’s principal tenor saxophonist, from 1944 to 1948.

1950s

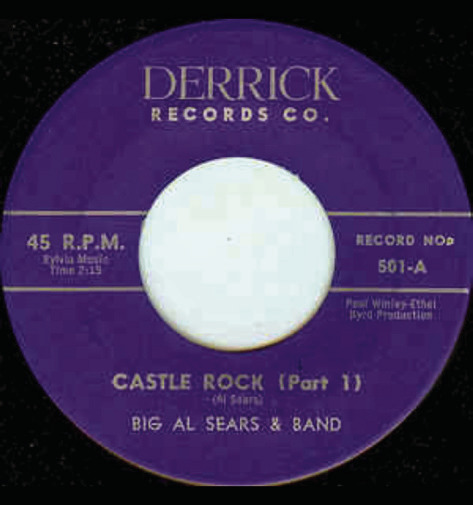

Sears became a member of the Johnny Hodges Band in the early 1950s. He was the lead player on the hit song that he composed, “Castle Rock.” During this decade, Al’s work gravitated toward rhythm and blues, and he had a noteworthy influence on the genre as it gained popularity. After leaving the Hodges band, he worked as a session player on many R&B records.

During the mid-1950s, Sears had a role in the emergence of rock-and-roll music. When popular deejay and promoter Alan Freed started staging big rock-androll shows, including his “Big Beat” television show, he was hired to lead the show’s band.

Freed and Sears’ band were featured in the 1956 movie “Rock, Rock, Rock.”

It was a prosperous time for Sears, but his performance career began declining in 1957 after Freed’s television show was cancelled, reportedly in part because Freed refused to stop using Black performers. The ABC network wanted only white acts for national broadcasts that included the segregated South.

By the late 1950s, Sears channeled his bandstand know-how into producing and publishing. He founded Sylvia Music Company, a publishing house named after his daughter. In the mid-century, owning, publishing and releasing records on artist-run or producer-run labels were among the few routes Black musicians had to protect their music, negotiate better royalty shares and build intergenerational value from songwriting.

Sears also worked as an executive at ABC Paramount. He had noteworthy success in battling for fairer financial compensation for Black recording artists including Ray Charles.

1960s to 1980s

Returning to jazz, Sears recorded an album of danceable music titled “Swing’s the Thing” in 1960. It marked the end of his recording career, but he continued performing into the 1980s.

After his performance at a jazz club in 1985, a New York Times critic wrote, “His playing … was just as strong, full-toned and expressive as it was when he played in the Duke’s series of Carnegie Hall concerts in the 1940s.”

1990

Al Sears died on March 23, 1990, in New York City.

Obituaries in major newspapers remembered him as versatile tenor saxophonist, bandleader and producer whose career spanned music’s golden ages and rock and roll’s breakthrough. At his funeral, the refrain was consistent: Sears made other musicians sound bigger, and made audiences feel welcome. That is the legacy our community celebrates – a Macomb native who learned to make a horn speak to everyone in the room.